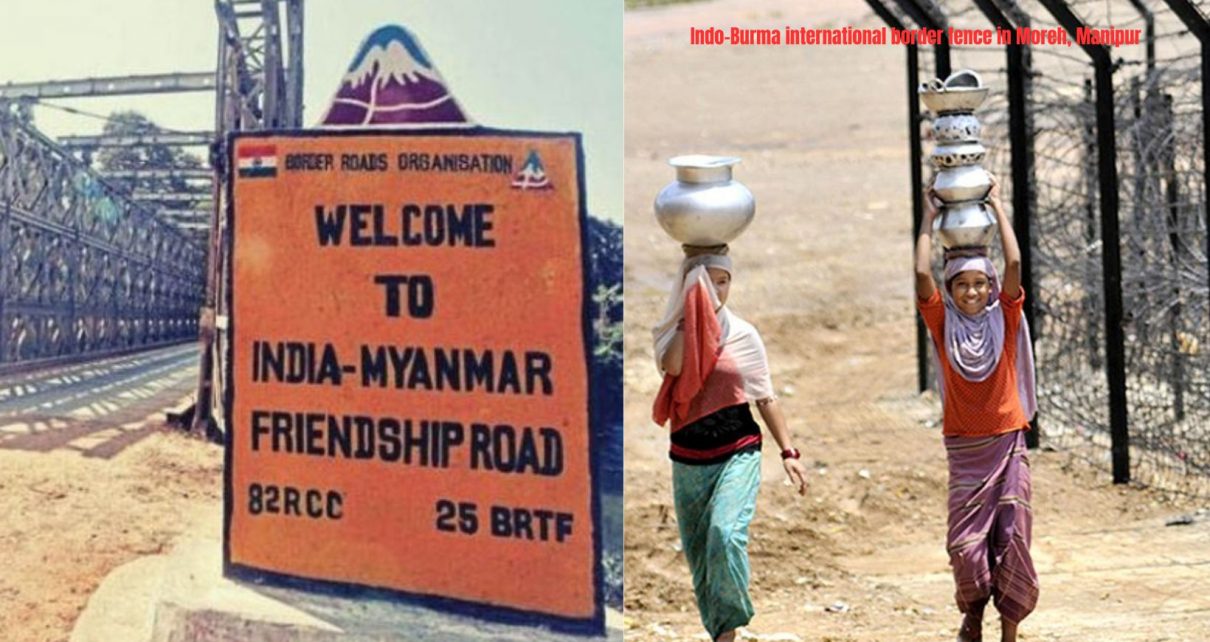

On 23 June 2024, five leading Kuki-Zo organisations from Manipur issued a joint statement against the Government of India’s decision to scrap the free movement regime (FMR) and fence the international border with Myanmar, urging people “to refuse to participate in any FMR-related activity”. The decision of the Government of India on 8th February 2023 to suspend the Free Movement Regime (FMR) between India and Myanmar and to fence 1,643 km long border with Myanmar has evoked reactions along the ethnic lines in India depending on the inhabitancy of the dominant communities on the Myanmar side. While the State Assemblies of Nagaland and Mizoram adopted resolutions opposing the Centre’s decisions, Manipur Chief Minister N Biren Singh appreciated the same. The tribal groups of Manipur however opposed the decision.

This paper calls for review of the decision to suspend the FMR and fencing of the Indo-Myanmar border keeping the long-term perspectives in mind.

Historically, the erstwhile British India included Burma until the enactment of the 1935 Government of Burma Act, the borders seldom existed and indigenous peoples living in both sides of the border travelled freely. After independence, Burma took cognizance of this reality and Rule 5(b) of the Burma Passport Rules of 1948 allowed “Indigenous nationals of those countries, whose land borders are co-terminous with the border of the Union, entering the Union by land who are members of hill tribes inhabiting areas adjacent to the land border” upto twenty-five miles from the land border. India reciprocated and vide notification dated 26 September 1950, the Ministry of Home Affairs amended the Passport (Entry into India) Rules of 1950 whereby the “hill tribes, who is either a citizen of India or the Union of Burma and who is ordinarily a resident in any area within 40 km (25 miles) on either side of the India-Burma frontier” were exempted from carrying passport or visa while entering into India. India and Myanmar regularly reviewed this arrangement including in 2018 allowing cross-border movement up to 16 km without a visa.

Free movement of indigenous peoples living in different countries is a common practice across the world. Therefore, Article 32 of the ILO Convention No.169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples binds the governments to “take appropriate measures, including by means of international agreements, to facilitate contacts and co-operation between indigenous and tribal peoples across borders, including activities in the economic, social, cultural, spiritual and environmental fields.”

Ethno politics and security scare since 2021 coup d’etat

Following the coup d’etat on 1 February 2021 in Myanmar, influx of Myanmarese refugees to India intensified. By the end of 2023, Manipur had received about 6,000 Myanmarese refugees, mainly belonging to the Kukis followed by Nagaland with 6,000 refugees, mainly ethnic Nagas, and Mizoram over 31,000 refugees, mainly ethnic Chins.

The reactions towards these Myanmarese refugees have been along the ethnic lines. While the presence of the Naga refugees in Nagaland has seldom been reported in the media as the Nagas accepted their ethnic brethrens, Mizoram welcomed the Chin refugees with equally with open arms. Manipur sought to raise the bogey of the Kuki refugees changing the demographic structure of the State and on 3 August 2022, the Manipur Assembly passed a resolution to implement National Register of Citizens in the State to weed out the foreigners.

Once the ethnic riots between the Meiteis and Kukis started on 3rd May 2023 in Manipur, the issue of Myanmarese refugees became one of the contentious issues. The Ministry of Home Affairs did not respond to the demands of the Meiteis throughout 2023 to scrap the FMR as the riots ripped apart the State.

However, the Myanmarese junta virtually collapsed after the intensification of the civil war since October 2023. The Myanmarese Border Guard Forces (BGF) are not in a position to man the borders in Chin State, Rakhine State, Sagaing and Kachin State on the Myanmar side. Insurgent groups have become the de facto authorities in these provinces of Myanmar.

The question remains whether suspension of the FMR and fencing of the Indo-Myanmar border ensure the internal security of the country and to maintain the demographic structure of India’s North Eastern States bordering Myanmar?

On the ground, the scrapping of the FMR has no effect on the ground as formal routes are not used for movement of people. Hundreds of Myanmarese troops and thousands of Myanmarese refugees fled to India using informal routes and not the FMR route. The Myanmarese refugees continue to be welcomed by Nagaland and Mizoram.

The fencing of the Indo-Myanmar border will take decades to complete and is unlikely to be completed before 2050 if one were to take the time for completing Indo-Bangladesh border fencing into consideration. It obviously does not address the security needs in the immediate terms.

India faces a classic failed state in Myanmar and it ought to take a more pragmatic approach based on the past experiences. At the height of the Maoists insurgency when the Government of Nepal virtually collapsed and the Maoists freely moved into India, India had not scrapped free movement agreement between India and Nepal despite declaring the Akhil Bharat Nepali Ekta Samaj as a terrorist organisation. Neither India closed the borders as Bhutan expelled over 100,000 ethnic Nepalese from the country and these Bhutanese refugees sought to return to their country via India.

Scrapping the FMR and fencing of the Indo-Myanmar border means de facto end to India’s Act East policy. Whether dealing with the junta or de facto authorities in Chin State, Rakhine State, Sagaing and Kachin State i.e. insurgent groups or any other future government after the end of the civil war in Myanmar, India simply cannot replicate its policy on Pakistan or Bangladesh towards Myanmar given its internal and external dynamics. India has to keep its Act East Policy alive and review the decision to suspend the FMR and fence the border.